September 22, 2016 marked twelve years from the day the pilot episode of Lost first aired. I took that as the appropriate time to dig out an article that I had saved from September, 2014, that celebrated the 10-year-anniversary of the show. That article led me to another tribute from the same time, and a host of links to lengthy Lostpedia bios and short clips from the show on YouTube. The two articles:

- Andy Greenwald, “The Lessons of ‘Lost’: Understanding the Most Important Network Show of the Past 10 Years” (Grantland; September 24, 2014),

- Jeff Jensen, “For the 10th anniversary of ‘Lost,’ Doc Jensen looks back… and forward” (Entertainment Weekly; September 22, 2014)

This post is gonna be a lot of thoughts borrowed from these two articles, plus a few of my own that I’ve held onto for years, as I muster a forgettable ode to an unforgettable television show.

Why now, though?

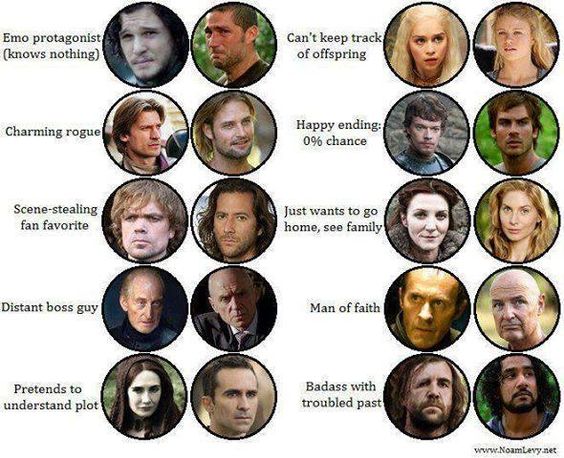

Because in 2016, we live in times when for about one quarter of a year, a certain show takes over public imagination and conversation so bloody much, that its fandom merits a study unto itself. Yet, what I’m surprised to see is that people are surprised to see this. Game of Thrones began when Lost ended, but few seem to remember that Lost had had the world in a similar frenzy – arguably much bigger, in fact – only half a decade ago.

Because part of the reason there is any frenzy for Game of Thrones (besides the loyal army of fans the books had already created) is the existing environment of television-watching that exists worldwide – an environment for which shows like Lost are almost single-handedly responsible.

Because as a culture nerd residing in India, I had grown completely disillusioned with Indian television by the time I was fourteen, which is exactly when Lost entered my life – and I mean it when I say that things were never the same again.

And because we all live on stories, and when the history of television would be written just before the end of man, Lost will be considered one of the biggest, most mindfuck endeavours in big, mindfuck storytelling – that never forgot either plot or character, suspense or drama, conversation or aesthetics.

(And also because, well, it did end up forgetting a bunch of those things.)

Biggest contribution: TV as a collective ritual

The most fun thing about watching an episode of Game of Thrones is NOT the spectacle OR the story, but the fact that everyone else is also watching. The second you finish watching an episode, you will head to the interweb to talk about what you just saw with everyone you know and everyone you don’t know.

This is not what watching television used to be.

Of course, there have been television shows in the past that became national and global phenomenons. The likes of M*A*S*H, Friends, Seinfeld, Roots, etc. got so many people to tune in each night they aired, it wasn’t even funny. In India, too, there have been many shows – soaps, comedies and even game shows – that everyone with a television set would tune in each night to watch together.

But what hadn’t happened was the internet. And the chance it provided for anyone who cares about anything to find others who feel the same, and basically go nuts.

Lost began in 2004 when the internet was light years away from what it is today, and more importantly, when social media wasn’t much of a thing. It was the first show that was genuinely so fucking engrossing, that people could not possibly keep all their thoughts and emotions about it to themselves, and found their outlet in a world wide web that was opening up exponentially. There were other good shows that came and went at that time (and many have since come and gone), but none made people spew approval, hatred, theories and fanboying with equal enthusiasm in the six days between any two episodes like Lost.

“Lost helped to normalize the idea that television can be watched intimately with millions of people not currently seated on your couch, and that episodes don’t end when the credits roll — they stretch and bleed into the rest of the week, through a dizzying scrim of chat windows, status updates, and ill-advised Googling”, says Greenwald in his article.

I must admit I wasn’t one of these internet nerds myself, and was restricted to reacting – albeit similarly – among my own little group of friends who had seen the show. But what I do remember distinctly is that it was definitely around the time of the first few seasons of Lost, that fan-driven content and wikis for TV shows started to become a thing. As Jensen says in his article, “Lost helped change the way we watch and talk about television. A once-passive experience processed the next day around the water cooler is now an interactive experience parsed immediately via social media, recaps, and blogs.”

Contribution #2: Nerd who?

As if this collective TV-watching ritual was not enough of a contribution, what Lost also did was make the weird mainstream. At any point in history before shows like Lost, Prison Break, Dexter and Heroes (ew) came around, it would have been considered a joke prospect to tell stories about smoke monsters and time travel and electromagnetism and immortality and magical numbers and the interconnectedness of the universe.

Yet, “Lost proved that there were viewers out there willing to accept all kinds of extreme stories as long as they were well told.”

And today, we live in times where the stories that stay with us the longest have been about methamphetamine dealers, hackers, cold war spies, dragons, and zombies.

The reason Lost pulled this off was that for the longest time, it never forgot that it is telling stories about humans to humans. I have zero training or knowledge in any kind of storytelling, visual or spoken or written or whatever, but I can confidently say one thing from my vast experience as someone who has been told stories through books, movies and television: nothing matters more than tapping into the audience’s humanity. Whether you’re making an action film, a comedy, or the kind of drama that we associate with awards season buzz. Whether you have a taste for the surreal or you like to keep your shots and editing at the most basic, restrained level. And whether you’re telling stories about devil incarnates occupying political office or about people stranded on a weird island. You cannot tell a good story without making humans matter.

This could mean making basic human emotions or tendencies matter in your story. Or it could mean making relatable human lives matter. Lost did both. Its structure of flashbacks and ‘flash-forwards’ that ran for the first four seasons, combined with each episode centered on a single character, is as juicy a recipe for exposition and character development as any. You got to see both the lives of the survivors in the ‘real world’, and also what emotional baggage they all carried because of their lives – how they were all ‘lost’. You got glimpses into cultures, regions, jobs, age groups, but also pain, determination, love and redemption. This meant that when the reveals came, or when the sacrifices came, or when anything came, it was more satisfactory. I will always cheer more if the human being doing things on my screen is a human being I know, understand or relate to.

And because Lost took so much care to make (each of) its many characters matter, it made it easy for its 20 million-plus weekly audience to also be interested in science fiction, mythology and fantasy. And mind you – this, on a broadcast and not a cable network or Netflix (yup, 20 million viewers each week).

What went wrong?

You. For thinking it was the finale.

No but, aside from dramatic opening lines to sections of a blog post only like four people will ever read, I do think that the biggest problem with Lost was not its supremely polarizing end, but the path it chose to get there.

Seasons 5 and 6 of Lost were a rollercoaster ride. The parallel timelines with survivors travelling time, the histories and the mysteries getting explored more frequently than ever. Except, like I said, caring about a rollercoaster that is being ridden by humans that don’t matter to you, is hard. Lost did such an excellent job with exploring people in the first four seasons, that it seemed to take that feat for granted as it stared in the face of its last two seasons with so many things left to show. The things took precedence over the people. And we had scenes with characters flashing through time not even looking at or talking to each other the way they used to – all establishment of their dynamics with each other forgotten, as each episode would become more concerned with the time-travel flashes and dropping hints about the island’s dozen, long-unexplained mysteries.

The two articles notice this too, when they observe how Seasons 5-6 “cultivated the notion that Lost was a puzzle to be solved, not a story to be enjoyed”, and how “the simplicity of the show’s macro narrative; the artful intricacy of the flashback storytelling structure; the poignancy of its gracious humanism; the adventure, the humor, all those glittering mysteries!—reminded those ultimately unfulfilled by Lost, of their misplaced faith, and what the show had become by the sixth and final season”. Because, “Episodes can be binged, but great characters ought to be savored.”

Still, it wasn’t so bad, and I recall the last two seasons still being massively satisfying. And even if you can’t forget the faults of the last two seasons (for the above reasons or for other reasons), you can remember Lost “as a swing for greatness that fell short, or as part of a movement that has stretched the medium and our expectations of it.” I would pick the latter.

The finale

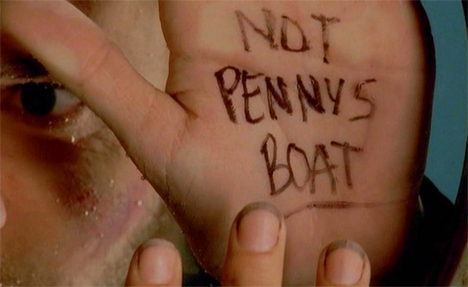

Speaking of expectations, let’s address this purgatory-shaped elephant in the room. I know SO MANY people, both personally and from what I read about the reception of the final episode, who absolutely HATED the show by the time it ended. People across the world wanted, not unlike the people on the island, some fucking answers. And Lost never gave many. Worse, it set up a ton of new ones.

Now I’m not gonna give those boring explanations for why the finale was actually okay, such as “No series finale can ever live upto all the expectations”, etc. And obviously, if you as a viewer had certain expectations from the show based on your own personal journey with it, I’m no one to demean that as a separate viewer.

But if those expectations arose for any of the reasons that it appears they arose for, I certainly would question these expectations.

Many people’s problem with the final episode, as with the final seasons, was that they “took a series that is deeply and richly psychological and character-based, and moved it into the realm of the allegorical”, or that “when Lost deals directly with the transcendental—rather than just glancing at it—the show can get awfully gooey, and painfully blunt.” These are quotes from top reviewers at The A.V. Club and Time. Coming from them, at least, I would have hoped for something a little better than “allegories are bad” and adjectives a little more descriptive than “gooey”. The answer to all this is: so what? What is so inherently wrong about a show that decided after a long time staying within the realm of the real and the observable, to take a leap into the realm of philosophy about the meaning of life?

Sure, the web woven around Jacob, the Man in Black, the Source, the forces of good and bad, and ‘destiny’, was a complicated one. Sure, the way the Mother spoke about man’s inherent corruptibility, and the way she described the Source, etc. can easily come across as less than ideally subtle – or because of that dreaded rollercoaster pace, just plain dumb. But neither can we deny that for four long years, we as viewers too were waiting with bated breath for the show to take a plunge into the unexplained, nor do I think is there even a point to setting up so many questions and then only restricting yourself to what you know and what is easy when you answer them. For each moment in the second half of Lost’s epic tale where ‘faith’ won over ‘science’, there will be a moment in the first few seasons where the show would refuse to confirm something transcendental, thereby forcing the viewer to restrict their imagination to the rational.

And even if the final two seasons’ reticent musings about life and death and good and bad might be considered failures, what certainly shouldn’t be so problematic is the purgatory. If one gets beyond the word (that would over time start to make it sound gimmicky), the ‘purgatory’ stunt was nothing but a return to the notion that these people were all kindred spirits to each other – people lost in the real world, found when they met the island and met each other. And so, they would only walk into that white light together, once each one had died, and each one had paid their dues.

Again, the execution of all these mind-boggling ideas may have been iffy – primarily because of the fast pace, and losing some touch with character in favour of plot. Sure enough, I had not even truly grasped the purgatory angle when I first finished watching the finale. And dealing directly with the transcendental IS always gooey, blunt and extremely difficult – just ask Christopher Nolan, whose Interstellar did exactly that in its climactic inside-the-black-hole scene by revealing ‘love’ to be the fifth dimension.

But it would be completely uncalled for to hate on a show that always played with such deep, challenging ideas, because it attempted to continue to do that till the very end. In fact, the unfathomable scope and surrealism of all the questions the show left us with is as good a merit as any.

In conclusion, a little indulgence

First indulgence: pitching Lost against Game of Thrones. I have played this game before, and round one went to GoT. But there are a couple advantages GoT has that we must note in round two. “Game of Thrones viewers don’t have the same “Do you have a master plan?” angst that Lost fans had: the series bibles are available at a book store near you.” The key difference here is that while Lost piled question upon question demanding explanations for ‘how EVERYTHING works’, on GoT, we know how things work; all that remains salivating over is ‘how will everything END’. Another advantage GoT has is that though Lost, for at least three long seasons, devoted much more actual time to character than plot, GoT has neither accomplished that, nor ever will – yet most crucially, is maybe not even supposed to.

The other indulgence is just a word about what a part Lost played in my life. It was only the second TV show I watched properly (in 2006 when I began, the definition of ‘properly’ had already become “not weekly on TV but whenever I want thanks to my good friend isohunt”), yet it gave me so much joy that watching a TV show or a movie very soon became much more than just entertainment for me: they are stories, experiences and journeys that make me think, make me feel amazed, and make me happy. Sharing theories about the Dharma Initiative and Jacob with friends in the ground where I used to play football for hours as a kid, imitating with others Sawyer’s accent and Jack’s facial contortions, or just getting excited about handing all six seasons with DVD extras to a new person interested in watching the show (sadly, a rare occurrence now) – what Lost did for me is not so different from what the island did for the survivors.

Live together, or die alone.